Culture Mechanics

Identity, types, and The Three Laws of Culture

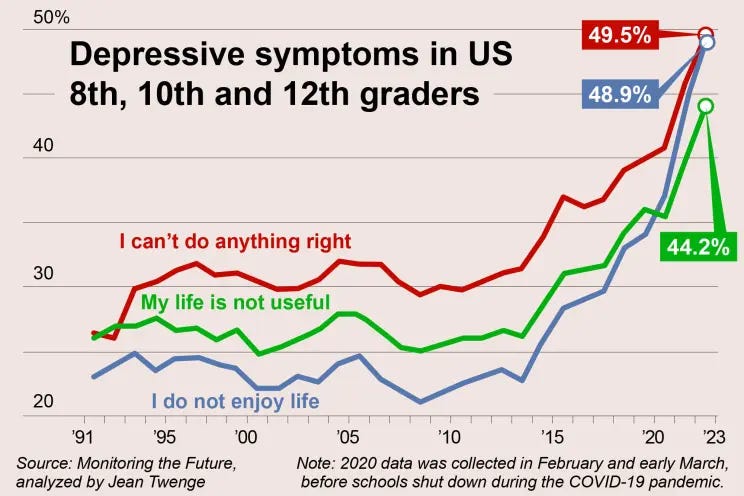

You’ve probably seen the stats. Anxiety and depression are up significantly among young people, especially teen girls. They’re making fewer friends too - five times as many now say they have no close friends as did in 1990. Suicides are rising even among children.

It’s not just them. Reported happiness has been declining since 1988, even as our existence has become more comfortable (and despite the implicit pressures to lie about happiness that such privilege entails).

Something’s changed.

There are many ways people try to explain these trends - smart phones and social media, algorithms, poor diets and declining health, atomization and a crisis of meaning - and I think there’s something to them.

But I have a theory you probably haven’t heard before.

It relates to a broad set of factors – the interconnectedness of the digital age, the democratization and globalization of status, the feedback loop between culture and media, and more – and how they have impacted culture and individual psychology. There’s been an orders of magnitude change in the factors underlying how individuals see themselves and others and how they relate to one another, and the process is only accelerating.

This series is in four parts:

I - Culture Mechanics, wherein I discuss the dynamics around status, identity, types, and illegibility, and how they fit together to form the three laws of culture;

II - Acceleration, in which I discuss the factors driving runaway acceleration of these dynamics;

III - Fallout, which covers their far reaching effects; and

IV - Depatterning, in which I discuss means for moving past these dynamics, and a positive vision for a life and culture without them.

I - Culture Mechanics

Status Games

The central problem for the individual is to find a safe way to be in the world. In the social sphere, this is about identity and status.

Your identity is an approximation of who you are in the terms of your culture, the result of an ongoing negotiation between how you understand yourself and how others do. It is based on your traits, values, preferences, abilities, social roles, and more; and it is something you both derive and construct in order to understand and present yourself favorably. Its significance is in enabling you to know both where and how you fit in and to actually do it.

Status is the end achieved through the means of identity. Status can be thought of as a rank ordering: how individuals in a given milieu stack up relative to one another. Your status is determined based on the esteem others have for you and their level of desire to ally with you; or from the other side, how unlikely it is that others will turn against you. Humans are a social species, and much turns on our prospects for cooperation with and support from those within our groups.

As a result, status is fiercely contested. (Note: it is low status to seek status – you wouldn’t need to seek it if you had it, and it’s considered unbecoming to be concerned with status at all - and so people find ways to camouflage these efforts.) In fact, status considerations impact nearly every choice people make, if in ways that are instinctual and largely beyond conscious awareness.

Status used to be largely determined by the luck of your birth and simple capacities and characteristics; and there tended to be strong barriers to competition, in physical and informational separation of the different social classes as well as in stricter norms regulating interactions between and among them. With all the many downsides of this arrangement, roles within it were for the most part at least relatively stable and straightforward — at least, outside of and beyond the cultural influence of the most centralized, incestuous arenas of power and wealth, where some degree of status hypercompetition has existed in every culture and era that enables them.

We’ve traded a society in which status was largely predetermined and unmerited but simple for one in which it is democratized and (more) meritocratic but extraordinarily complicated, and increasingly so. This was not without tradeoffs. Status has become central to every feature of our lives as people have searched for ways to differentiate themselves and outcompete others against a backdrop of mounting pressure, complexity, change, and uncertainty.

Even merely fitting in has become an extraordinarily difficult task, more so than people commonly recognize because it’s come to feel normal to them. In what follows, I am going to try to show you what the air you’ve been breathing is actually like.

The Three Laws of Culture

People are familiar with stereotypes, for instance based on race, where you grew up, what kind of job you have, etc. But that is just the tip of the iceberg. In our society, everything connotes a type: the minute details of how you speak, like your word choice and intonation; your style, taste in music, the tv shows you watch; and deeper qualities like your opinions, philosophy, politics, sense of humor – and on and on.

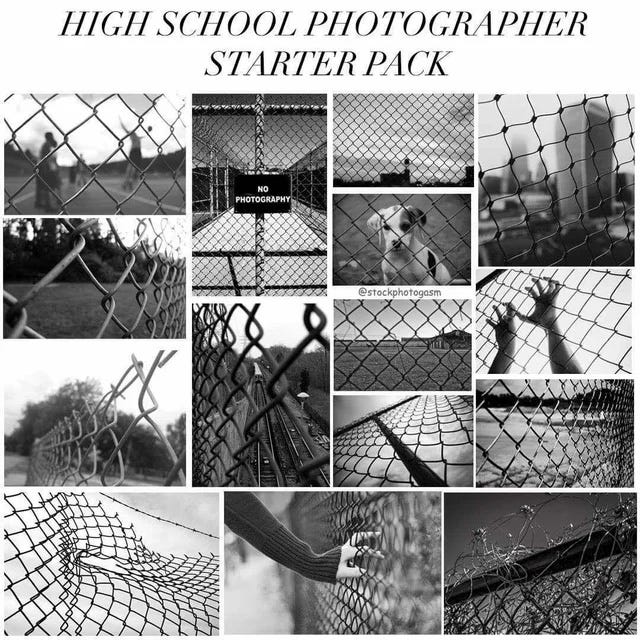

Here are a few popular examples from the StarterPacks subreddit:

I’ve deliberately chosen examples unlikely to apply to readers (currently, at least) because I hate how reductive and mean these can be. But they should give some insight into how specific, subtle, and strangely powerful types can be, and why people would take pains to avoid fitting them. What the types in these images are fundamentally doing is to associate traits, and imply that if a person has one, they have many. Generally, types are rules that connect the ways you express yourself and present to society to who you are at your core.

This is the first law of culture:

1. Status is negotiated through identity, and identity is negotiated through types.

The choice of beard for instance has regrettably come to connote something about a person’s values and character. And even more unfortunate is that these kinds of types are often accurate and useful in helping us navigate the world. There really are ‘spiritual’ guys like that, and you can save yourself a lot of trouble by seeing through their bullshit upfront. Types help us to make decent judgements in real time about who we’re likely to get along with and who we are not; and, as I discuss later, they also enable the group to reign in the bad behavior of individuals.

What makes types different from standard associations is their social dimension. Natural Hazard put it well in his post on the subject: “Types are more than patterns. Most patterns we observe never get reified with a phrase or a handle, and most patterns that we individually reify never get ratified by a social network.” Types are patterns that are broadly understood and easily deployed in communications with others. They are the prevailing conceptual vocabulary of a culture, and the means by which its members tend to understand one another. Put another way, types make the individual legible to the group.

Legibility in ordinary usage relates to being literally readable, as in the context of deciphering the worn pages of a tattered manuscript. In the social context, legibility means that others can understand you in terms of a shared conceptual vocabulary by slotting you into types; and precisely because it is shared, this understanding can be weaponized against you. Being legible means being vulnerable to deconstruction by your peers into connotation laden, broadly understood boxes, and this is a genuinely deep vulnerability.

If you can remain illegible, you avoid two problems: at one end, you are afforded a layer of protection from unfair, reductive stereotypes and connotations; at the other, you are enabled to gain status through bullshit and pretense. Conversely, if others in a group are able to make you legible, they are able to prevent you from gaining unearned status, but also to increase their status by reducing yours.

These incentives lead to the second law of culture:

2. Individuals strive to remain illegible to the group, and the group strives to make individuals legible.

It’s not that there aren’t ever advantages to being legible. For instance, people trying to build a following want to be legible in certain ways – you have to have something associated with you that people can grab onto. And as I was getting feedback on this post from close friends, one mentioned this:

I think I find myself trying to lean into a few types - accepting the good with the bad - to avoid the stress of constantly needing to identify and cultivate illegible elements for my identity. It’s helping! But it comes with a certain amount of giving up on being strictly cool and embarrassment.

In other words, he is forgoing the marginal rewards of niche status hypercompetition in favor of a sturdy, reliable, no-hassle identity. Most of the benefits of type status competition are in the social spheres of dating and friendship, and so I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this is happening after he’s developed a strong network of friends, and is in a long term relationship approaching marriage. The social trends of fewer friends and less dating and marriage among the young would suggest people are aging out of this status competition later and later - and perhaps increasingly not at all.

It’s also not that there aren’t ever positive types either - they just don’t tend to last long. There are two ways this happens.

Case #1: The positive type is only ‘positive’, and is in reality based on bullshit and pretense yet to be decoded by the broader culture. Other individuals in the culture seeing this bullshit unfairly rewarded then have an incentive to work out what exactly is happening; and as they come to understand it bit by bit and communicate this to others, a shared understanding begins to emerge. This takes the form of a type.

It is a type that is being leveraged when a young woman at a bar feigns enthusiasm with thinly suppressed amusement as a guy brags to her about where he went to college, his job, or who he knows; when your friend in academia impersonates his pretentious colleague in philosophy; or when a mother introduces her brooding and recalcitrant teenage son to neighbors and says with a wink, “he’s too cool to say hello”, and they knowingly smile.

A personal example from my childhood involves Harry, far and away the coolest kid in my middle school. His friends were mostly in high school; he listened to music that none of us had heard of, had good style, and even played shows with legitimate bands. And he had many other genuinely positive qualities - he was very funny, and had real charm and dynamism. We all wanted to be like him and felt inadequate by comparison. But a band we all liked – in part because of his influence – released a song that laid it all bare:

Despite your pseudo-bohemian appearance

And vaguely leftist doctrine of beliefs

You know nothing about art or sex

That you couldn’t read in any trendy New York underground fashion magazine

Prototypical non-conformist

You are a vacuous soldier of the thrift store Gestapo

You adhere to a set of standards and tastes

That appear to be determined by an unseen panel of hipster judges (bullshit)

Giving a thumbs up or thumbs down to incoming and outgoing trends and styles of music and art

Go analog baby, you’re so post-modern

You’re diving face forward into a antiquated past

It’s disgusting, it's offensive, don’t stick your nose up at me

Say Anything, Admit It!!!

I didn’t really get any of this at the time, but some of my friends did. And as the culture shifted over the ensuing years, Harry stopped being as cool. Though I don’t know what happened after high school, he seems to have been a case of peaking early – perhaps in some ways a victim of his abilities, because many of us would have gladly taken his place if we could have pulled it off.

Case #2: The positive type is based on genuinely positive behaviors, traits, and qualities. What happens in these cases is that others adopt these behaviors because they want to be seen favorably by their peers. But the problem is that they tend not to want to do the much larger amount of work to really embody the trait, and so they merely take up the low hanging, superficial elements of the behavior.

But this is the same kind of bullshitting and pretense as in the first case, and the result is once again that the broader culture now has a motivation to make this bullshitting legible so that they can reign it in. This is accomplished by typing the behaviors, and the genuinely positive instances are collateral damage. This process can even be stoked by competitors acting in bad faith, one way that being legible creates a handle by which others can grab and manipulate you.

These dynamics are what's happening on the ground driving the macro phenomenon in David Chapman’s analysis of subcultures:

Subcultures were the main creative cultural force from roughly 1975 to 2000, when they stopped working. Why? One reason—among several—is that as soon as subcultures start getting really interesting, they get invaded by muggles, who ruin them. Subcultures have a predictable lifecycle, in which popularity causes death.

Illegibility is a buffer against this kind of terminal popularity. If the masses can’t easily understand something, fewer will adopt it; and those that do will be unable to adopt it with any kind of high fidelity, leaving room for the true adopters to differentiate themselves.

As an example of something positive becoming negatively typed in this way, consider the phenomenon of clichés.

What exactly happens when something becomes clichéd? Something - a phrase, a plot device, a style - had the quality to become popular and widespread, but then becomes too popular. Wanting to associate this quality with themselves, the masses use it inappropriately in contexts lacking its original motivation and inspiration. Adopted widely and replicated poorly, its repeated misuse comes to dominate its cultural associations, and it becomes typed.

Clichés demonstrate the extent to which being typed can thoroughly tar something regardless of its other positive qualities, and why people work so hard to avoid them and remain illegible. Think of how strange it is that the behaviors, attitudes, styles, and possessions that were high status in the previous generation now elicit cringes and second hand embarrassment.

These dynamics are the basis for the third law:

3. High status things tend to be illegible, and illegible things tend to be new.

This law is responsible for much of what happens in culture. It’s what drives fashion evolution, for instance. Something new and high status comes along, and once legible, it draws in the masses until they destroy it. Trends do return, but only once their old cultural meanings and associations have faded and they have the freedom to become something new.

It’s also part of why culture reliably cycles between generations and why generations tend to clash. The young and those with few identity commitments have a natural advantage in this process, and they vie to take status from those who already have it by undermining the structures and norms of their elders in favor of their own – think ‘ok boomer’.

The result of all of this is that being legible is a vulnerability much of the time, regardless of whether it happens through a positive or negative type - being described is the prelude to being attacked. And so people aim to exist in the negative space between unfavorable types, and to earn stature through ordinary virtues and prevailing cultural currents without ever becoming too legible.

This complicated dance is part of what’s behind interest in celebrity culture. Prior to the social media era, pop culture was the arena in which the prevailing types and the most advanced strategies to navigate them were fully on display, and people have a deep natural interest to know what works and what doesn’t. It’s become less centralized as a result of social media, and now everyone is showcasing their strategies, with the successful rising to influencer and even celebrity stature.

The Three Laws of Culture

Status is negotiated through identity, and identity is negotiated through types

Individuals strive to remain illegible to the group; and the group strives to make individuals legible

High status things tend to be illegible, and illegible things tend to be new

The combined effect of these laws is an ecosystem in which people are ever on the run from their peers; trying to form and maintain a ‘safe’ identity within a shifting matrix of complex associations that is always looming in the background threatening to swallow them.

If that doesn’t sound bad enough, here’s the thing: this is accelerating.

Very interesting read, I'm looking forward to the rest of the series!

One idea that crossed my mind while reading is the role that authenticity plays with regard to status and illegibility. It seems that the power offered by typing someone and making them legible is at its greatest when that person is "pretending" to be that type, or taking inauthentic actions so as to try and be someone they are not. You do not "gain any power" over the man who is actually, authentically into spirituality when you type him into the framework shared above (though the existence of that framework may affect how people think of him at first glance); nor does the high school photographer who actually, authentically enjoys taking pictures of fences feel much embarrassment when typed as above. However, both the man who is into spirituality as a path to sex and the high school photographer who takes pictures of fences to be "cool" have much to lose by being typed / becoming legible. Legibility seems to matter most when people are playing pretend, as seeing through the act means you also know they are a person who pretends (following the types of others), rather than choosing their own unique path.

It seems being authentic may offer a potential path out of this "ecosystem in which people are ever on the run from their peers"; the associations in the background lose much of their power if your type is simply you, rather than an act. That being said, the line between being "you" and "pretending" can be a blurry one, due to the heavy influence of environment and culture on who we become. Being "you" is not always straightforward, and even with self-reflection it can be hard to parse out ("am I into spirituality just for the sex?" can be a hard question to answer unbiasedly).

I really like how you have boiled down culture to some general principles. They were not immediately obvious to me - but after pondering them your three laws make a lot of sense, and are quite useful for thinking about how culture evolves.

Were there any blog posts / books / other forms of media that strongly influenced this work? I'd like some more background to read on this series.